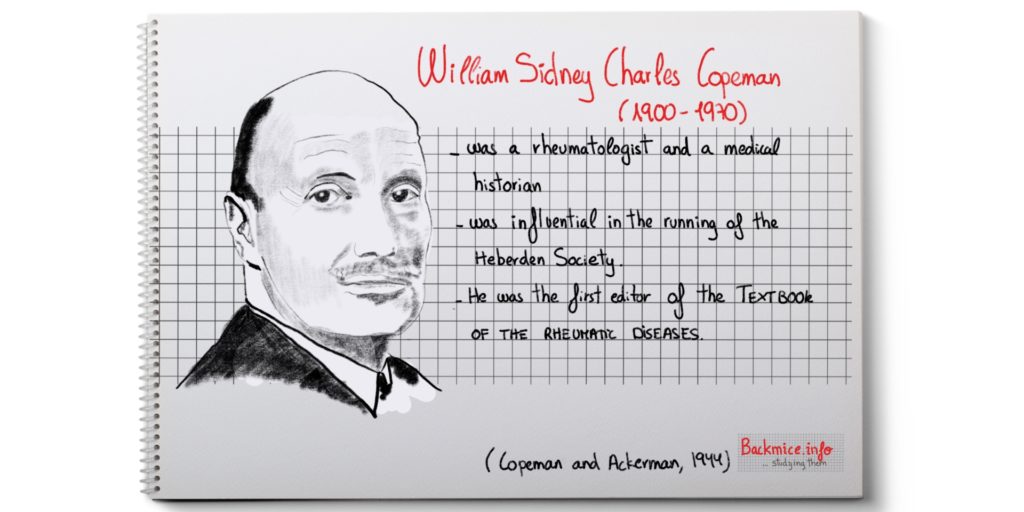

This is a rather long article published in 1944 in a magazine named Quarterly Journal of Medicine by Copeman and Ackerman. This article had a big impact on those days and many posterior articles related to back mice refer to this one. I would say “this was the article that changed everything”. Unfortunately, due to what I call the “discopathy fever”, Copeman’s works and many others have been completely neglected in the last 50 years. As the role of fibro-fatty tissue (as back mice) as a causative agent in “rheumatic pain” or the role of the peripheral cutaneous nerves in explaining certain pain syndromes (as cluneal neuropathy) have, too.

I consider this article an “indispensable-to-read article”, since it was the “first try” to explain many pains that today are still labelled as UNSPECIFIC PAINS. And what is even more surprising is that it was done under WAR CIRCUMSTANCES. Copeman and Ackerman were intrigued to understand what were the underlying pathological mechanisms to produce such severe pains as LUMBAGO in rather healthy soldiers.

They careful did 14 dissections to study certain fibrositic plotted points. They found out that “fibrositic pain” appears to have a topographic relationship to what they called “the basic fat pad”.

LINK to → The term “fibrositis”

(Personal note: This work was underdone during war, and they dissected just MASCULINE CADAVERS. I wonder if the conclusions could be completely extrapolated to women, since women may present a thicker or different fatty layer).

Copeman and Ackerman, by proceeding with the cadaver dissections, surprisingly found that the SYNOVIAL FAT (the fibro-fatty tissue that surrounds the tendon sheaths) could explain some cases of tenosynovitis, since it can easily become edematous and completely surround these structures. They describe certain locations.

In cases 7 and 8, Copeman and Ackerman made reference to what they called “BUBBLE OF FAT”. I personally understand that this would be caused by the “accumulation of fluid under the fibrous capsule that surrounds the fatty lobules”. In case 8, they even explored the site that received previous injections of the TRIGGER POINTS surgically and observed that the “bubbles were less tense”. (Personal notes: It seems that the fatty lobules that contain a capsule can sometimes present edema in form of “bubbles” under tension. “The trigger point injections and the acupuncture” could work in reducing the pain by PUNCTURING the fibrous capsules and letting some tension out).

It is also worthy to emphasize that they incised patients that presented PALPABLE NODULES BUT also patients that just presented PAINFUL SPOTS, in both cases under the subcutaneous tissue they observed tense fatty lobules, herniated or just tensed and sometimes just “bubbles”. After removing or teasing them, the pain disappeared. SO IT SEEMS THAT SOMETIMES THE FIBRO-FATTY TISSUE IS UNDER TENSION CAUSING PAIN BUT IT IS NOT EASILY PALPABLE (Summary: Backmice are not always easily palpable as a nodule and it would present as an EXQUISITE PAINFUL SPOT on unidigital pressure).

Copeman and Ackerman analyze all the fat removed in the biopsies they performed microscopically. Their findings are similar to other authors’s referring that there is “normal fat tissue” but they observed, as some other authors did, young cellular fibrous tissue growing into it, congested blood-vessels with thickened walls and some perivascular proliferation.

They also concluded that the cases they report represent advanced stages of fibrositis, they hypothesize that the pain in all cases of fibrositis

could be due to a temporary or permanent increase in TENSION of the fibro-fatty tissue, which is confined in a NON-DISTENSIBLE fibrous covering or sheath. This condition would happen mainly along the borders of the muscles.

They observed cases where the “whole fatty tissue of the zone” was actually tender, even in “one thin pyrexial patient” they could observe the fat bulging visible beneath the skin.

They also observed that the terminal fibrils of the nerves arborizations were found mainly finishing at the fat lobules.

They also theorize that the fat tissue “being a primitive tissue” becomes easily edematized especially if its blood-supply is defective. The removal of this excess of fluid is done by the lymphatic system. In early stages, this could explain the rapid resolution of symptoms. But if the edema persists, the tension increases and a tendency of herniation may occur especially at the weakest points of the fascia covers, ultimately with the eventual formation of PALPABLE NODULES.

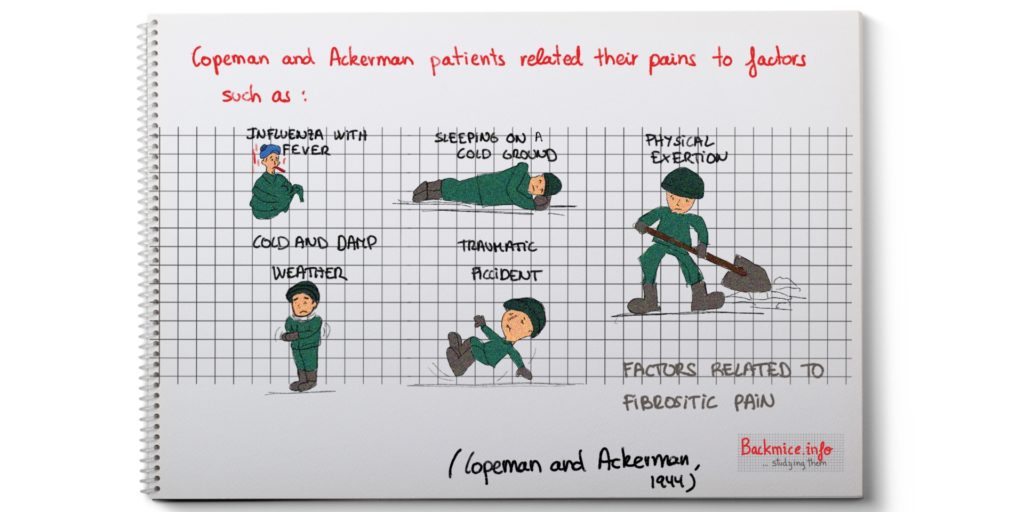

Copeman had previously observed that the “PAIN IN THE BACK” which accompanies most PYREXIAL illnesses such as influenza, exanthemata, malaria, dysentery, and infective hepatitis shows a certain pattern related to the presence of these TRIGGER POINTS. Moreover, once the acute phase of the illnesses passes away, the TRIGGER POINTS PERSIST unknown to the patient in a proportion of cases. Copeman theorizes that could be the BASIS OF FIBROSITIS, which later would activate again after certain infections or injuries.

IT IS REALLY A PITY THAT PROBABLY DUE TO THE WAR and the TECHNICAL LIMITATIONS BY THEN, THEY COULD NOT SHOW ANY ILLUSTRATIVE PHOTOS OF ALL THE “BIOPSIES” THEY PERFORMED.

NOTES ON THE ARTICLE:

‘Fibrositis of the Back’

By W.S.C. Copeman and W.L. Ackerman

Introduction: Copeman and Ackerman perform this study under war circumstances with the soldiers.

Copeman and Ackerman introduce the article by making the following statement:

“The authors believe that the ground covered by this study has not previously been systematically explored”.

They comment that they carried out the study during “active service” (Second World War) and they could not have access to any relevant medical papers.

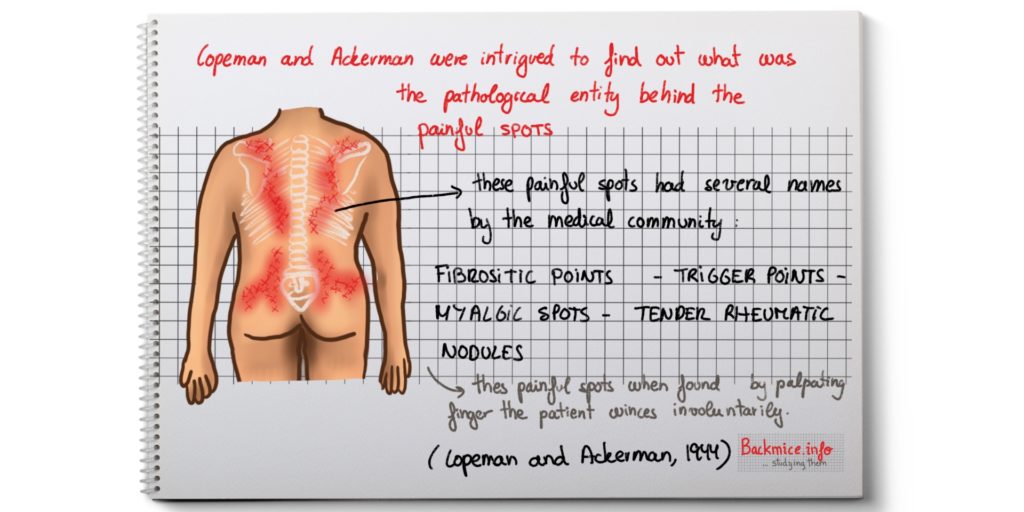

They got intrigued by the condition named “fibrositis” since they observed a high frequency of “fibrositis of the back” among otherwise healthy young army man.

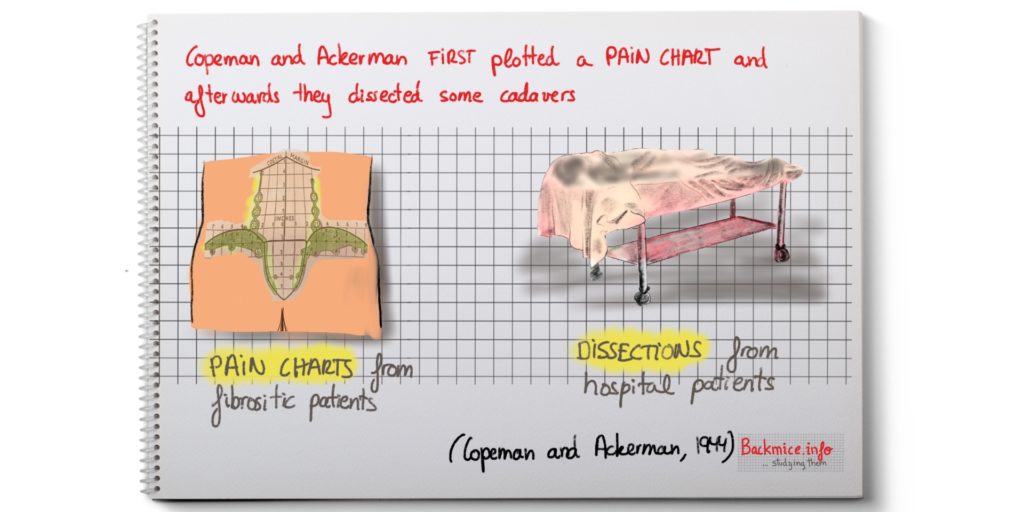

They first plotted a PAIN CHART where they took note of every exact painful point from the sufferers.

They later DISSECTED the back of every patient that died in the hospital to examine those areas.

As a result of this and the subsequent clinical observations and BIOPSIES, they reach certain conclusions to explain certain cases of “fibrositis”.

“Fibrositis of the back” WAS A WELL-RECOGNIZED clinical entity although its etiology was not clear. Copeman and Ackerman mentioned that Comroe, in 1942, stated that “the etiology is unknown and that there are no specific pathological lesions”.

They also mention that Kellegren pointed out that pain generally had its origin in CERTAIN FOCAL POINTS, from which a more generalized subjective pain is referred according to a SEGMENTAL PLAN. This referred pain may be at considerable distance from its real origin (as it is exemplified by sciatica, where origin can be located at the lumbar/gluteal region).

These PAINFUL spots, which have been named TRIGGER POINTS, TENDER RHEUMATIC NODULES or MYALGIC SPOTS, are clinical entities. When they are found by a PALPATING FINGER, the patient winces involuntarily. Pressure of the same intensity a few millimeters away from those does not produce the same response. There can also be a degree of a more generalized muscle tenderness. By pressure of this painful spot, the referred pain reproduces. The injection with LOCAL ANESTHETIC IN THE EXACT POINT usually resolves the pain successfully BUT OFTEN localizing the CENTER OF THE POINT is not an easy procedure.

The peculiarity of the “PARAVERTEBRAL TENDER SPOTS”, tenosynovitis?

Copeman and Ackerman mentioned that the TENDER SPOTS located about two inches on each side of the spinal column in the dorsal area did not appear to them to occur in fixed positions. And the pain arising from them presented certain differences with the rest.

1-They rarely present REFERRED pain to a distance.

2-Pain seems to be produced by the contraction of the muscle group.

3-The onset of pain seems to be preceded by localized stiffness of gradual onset.

4-When palpated (especially after massage) it feels like they present an ELONGATED FIBROUS STRUCTURE which can be rolled beneath the finger.

5-If the patient moves while pressing it, a DISTINCT CREPITUS such as the one that occur in TENOSYNOVITIS can be felt.

Taking all these points into consideration, they considered that the PARAVERTEBRAL TENDER SPOTS would be related to a tenosynovitis of the terminal tendons. They CONFIRMED this theory by dissection of the area.

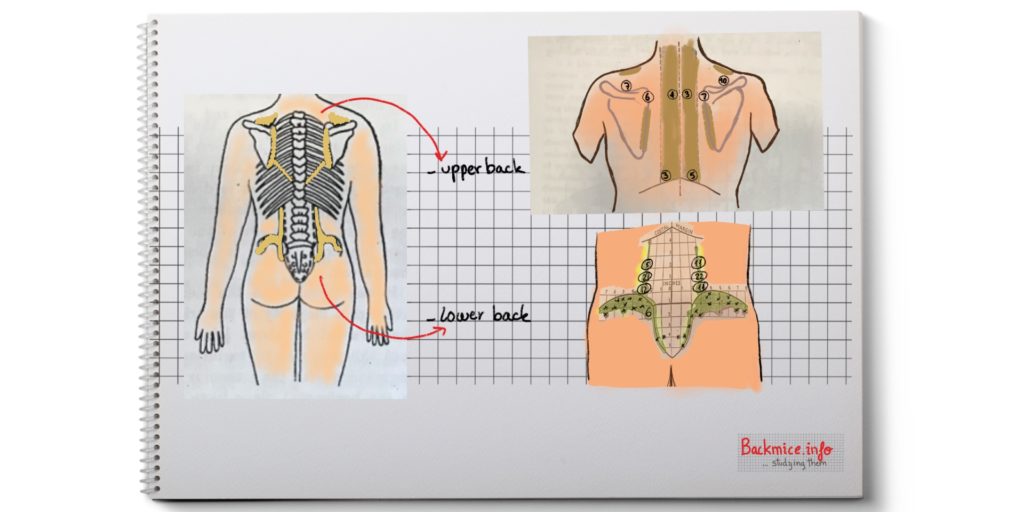

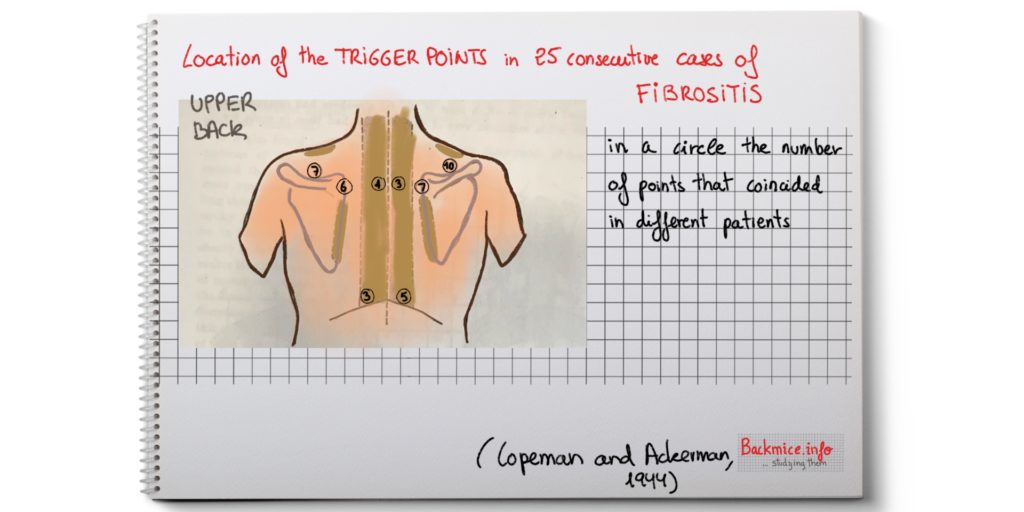

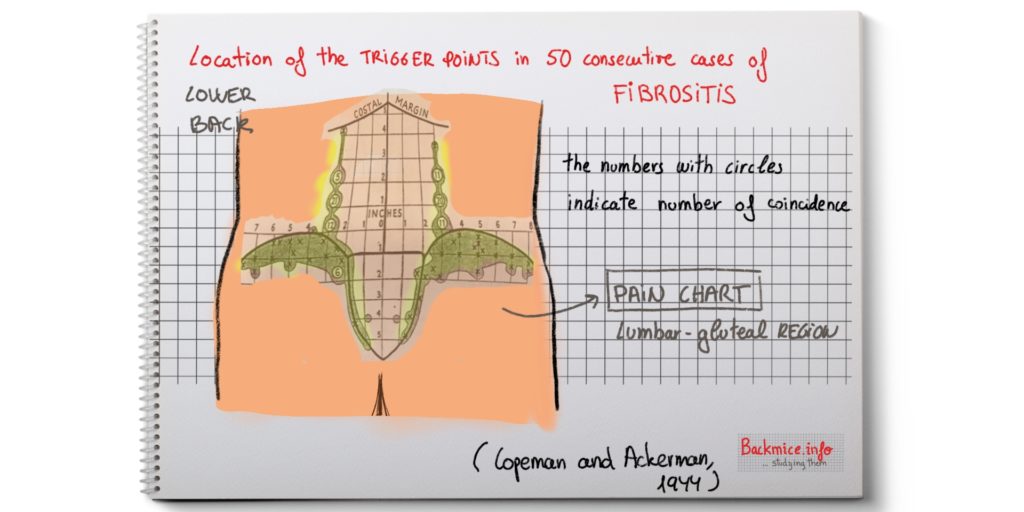

Copeman and Ackerman plotted the sites of the typical “firbositic pain”, they present charts.

Copeman and Ackerman took measurements in a large number of patients suffering from CHRONIC FIBROSITIS and from more transient pains occurring during other illnesses, and clearly they found out that they present the SAME TENDER SPOTS.

In the figure they show the PLOTTED aggregate of these sites.

-In the DORSAL REGION, the most constant POINT of tenderness is found over the SUPRAESPINATUS TENDON, it just passes deep to the acromial process of the scapula.

-In the INTERESCAPULAR REGION, tender spots may occur anywere in the vertical plane within 2 and 1/2 inches of the midline (it represents the width of the sacrospinalis muscles at this level).

-ALONG THE MEDIAL BORDER OF SCAPULA: from the level of its spine downwards.

-An area where the lower costal margin crosses the line of the outer edge of the sacrospinalis muscle is also a common site.

-In the LUMBAR REGION, at the edge of the sacrospinalis muscle just above the iliac crest, one inch above this level, and at the level where the latissimus dorsi crosses the sacrospinalis.

-In the gluteal region, points may be found along the crest of the ilium and 2 inches below. Also along the sacro-iliac junction.

Copeman and Ackerman dissect 14 CADAVERS

Copeman and Ackerman dissected 14 cadavers paying attention to the FIBROSITIC sites that they previously PLOTTED in consecutive patients.

After 1 or 2 dissected bodies they had to modify their preconceived ideas. They expected to find LESIONS IN THE FIBROUS TISSUE, but they could not find abnormalities or adhesions. They realized that the PLOTTED POINTS corresponded exactly to what they name “basic fat pattern”, which were certain fat deposits that presented even the most cachectic bodies.

They noticed that in the ANATOMY BOOKS there was not much information regarding the fascial layers and deposits of body fat.

Deep to the subcutaneous fat and the areolar tissue lies the highly vascular SUPERFICIAL FASCIA which forms a continuous sheet from the neck to the gluteal region.

The space between the superficial and the deep fascia seems to be a “potential space” for the major part of the back containing little or no fat.

However, in certain WELL-DEFINED places there are deposits of “pinkish fat” between these two fascial sheets.

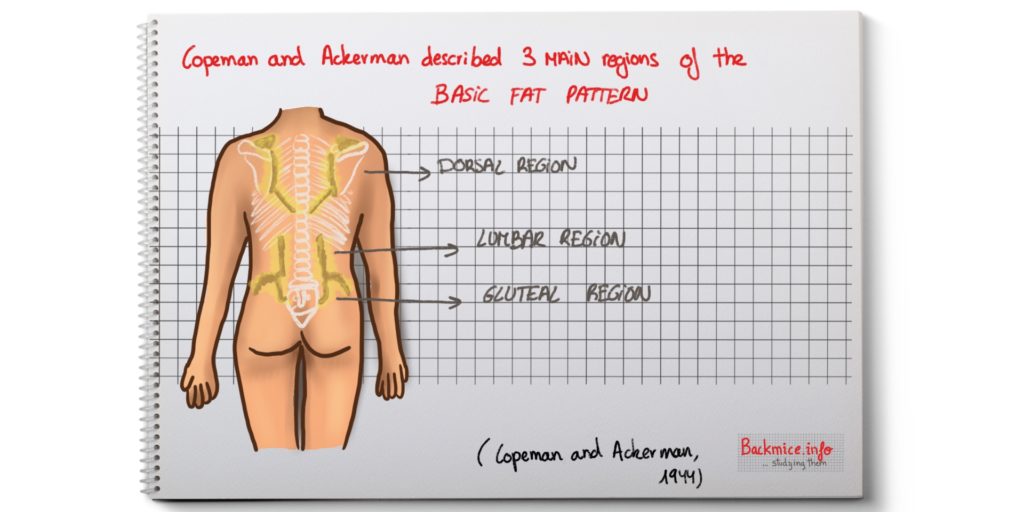

Copeman and Ackerman named “basic fat pattern” the well-defined fat deposits between the two fascial sheets and in equally constant deep areas.

The “basic fat pattern” was present even in cases of cadavers that presented an extreme cachectic state (after being in coma) and most of the body fat had disappeared elsewhere.

In obese people, this fat pattern tends to be obscured by the presence of a more generalized deposition of fat.

They also noticed that the fascial layer was not uniform in thickness, in some places it was notably thinner and they found certain deficiencies, then the underlying fat tended to bulge through resulting in a complete herniation (fat hernia).

Copeman and Ackerman described “the basic fat pattern” they found in dissected cadavers

Copeman and Ackerman explained it in 3 parts

DORSAL REGION BASIC FAT PATTERN

It is found lying along the tendon of the spuraespinatus muscle, it becomes incorporated into the synovial sheath of the tendon and continuous with that of the deltoid bursa.

In two edematous bodies, edema of this fat appeared to have caused some constriction of the tendon at the point where it passes deep to the acromial process.

It is also found deep to the investing fascia of the trapezius muscle, outlining its borders.

A similar appearance is found at the medial border of the scapula, from the root of the spine downwards.

In two bodies, small flattened herniation of this fat through the fascia were found; in a third body fat herniation was caused while applying pressure near to an obviously weak spot in the fascia.

There are also fat deposits in the synovial sheaths of the tendinous portions of the sacroespinalis muscles, especially in thin type of specimens.

Copeman and Ackerman mention again that the fibrositic pain that the patients present in that region of the scarospinalis tendons and the suprespinatus tendons would be more related to a SYNOVITIS OF THE TENDON SHEATHS in these locations.

By detailed examination of the synovial sheaths of all the tendons and joints, Copeman and Ackerman found that the synovial sheaths consisted largely of fibrous fat, which forms a loose tunnel through which the tendon moves. The tendons are themselves avascular and their microscopic structure does not suggest that they become edematous. They consider that it’s the tendon’s investing fatty capsule which become edematous, thus narrowing the lumen where the tendon moves.

This hypothesis of the causation of the tenosynovitis is supported clinically by the sequence of the onset of NONTRAUMATIC synovitis in any joint, which starts generally with period of stiffness and tightness which preceded the pain by some hours, which would represent an increasing compression of the tendon. In certain anatomic spaces, the secondary joint could be affected by joint effusion. In the sacrospinalis tendons it would not happen.

Another place with common painful spots is around the lower costal margin. It is located at the junction of the lower costal margin and the outer border of the sacrospinalis muscles. Dissection of that zone reveals the presence of two or three FIBROUS BANDS, which cross the sacrospinalis at this region, constricting it where they do so. (The may represent a common variant of the serratus minor posterior muscle). As they dissected that muscle, the underlying fat seemed to them to be UNDER CONSIDERABLE TENSION so it buldged out when the muscle was divided.

LUMBAR REGION BASIC FAT PATTERN

The sacrospinalis muscle is edged with fat: some lying superficial to the deep fascia (LUMBAR FAT PAD) and some lying within the angle made by the deep fascia as it splits to invest this muscle. In the very wasted bodies, the upper portion (covered by the latissimus dorsi) this fat is deficient. Below this, the fat follows the line of attachment of the deep fascia and the muscle along the sacroiliac junction. (They frequently observed fat hernias in these areas).

They also realized that there were some variations of the “plotted trigger points” in accordance with the basic fat pattern and the muscular development of the subject.

Copeman and Ackerman also realize that, at the lumbar region, the CUTANEOUS BRANCHES OF THE POSTERIOR PRIMARY RAMI of the first three nerves (or cluenal nerves) PIERCED the DEEP FASCIA after leaving the muscle. THEY CROSS through a definite FORAMINA accompanied by small blood-vessels.

They observed that in two bodies a small TUFT of fat lobules was protruding through the foramen.

They also described that the fascia presented a small horizontal fold acting probably as a valve preventing herniation of fat when the back is flexed. They theorized that maybe the LUMBAGO could be explained by a herniation of fat due to a deficiency in the valve function.

THEY also described BUBBLES OF DEEP FASCIA, especially along the edge of the sacroespinalis muscle, the bubbles of fascia containing a few lobules of fat would be bulging up from the angle in which it is contained. By firm pressure applied adjacent to these structures, it can easily convert into a true FAT HERNIA the size of a pea or larger. They hypothesized that this potential fat hernia would not give rise to symptoms UNTIL a trauma or a pyrexial illness would mean that the patient would lie on his back for several days, then an increase in the pressure and a painful distension of the fat lead to edema which could perpetuate the condition.

GLUTEAL REGION BASIC FAT PATTERN

In the gluteal region there is a “crescent of pink fat”. It extends along the crest of the ilium and for a distance of about two inches below. IT IS CONTAINED within the superficial fascia. It extends from the anterior superior spine back to the sacro-iliac junction, often sending a narrow prolongation down this area. In the same region but deeper, there is a similar “tongue of fat” in a deeper level (it is continuous with the one of the edge of the sacroespinalis muscle).

The FAT of the ILIAC CREST LIES IN LAYERS, where it HAS SPLIT THE SUPERFICIAL FASCIA in which it is contained. It is common for the LOBULES of one layer to herniate into a more superficial one or laterally into an adjoining compartment where the fibrous walls are weak or deficient. This fat lies ALMOST DIRECTLY over the unyielding bone of the ilium, this may account for the common occurrence of such lesions in this area.

They found that the nodules (back mice) and trigger-points correspond to FAT LOBULES HERNIATION THROUGH FASCIAL WEAKNESS

Copeman and Ackerman found that the herniation of fat lobules through fascial weakness, deficiencies or foramina was not infrequent in the course of dissection, and they were convinced that this lesion could be related to the “fibrositic pain”.

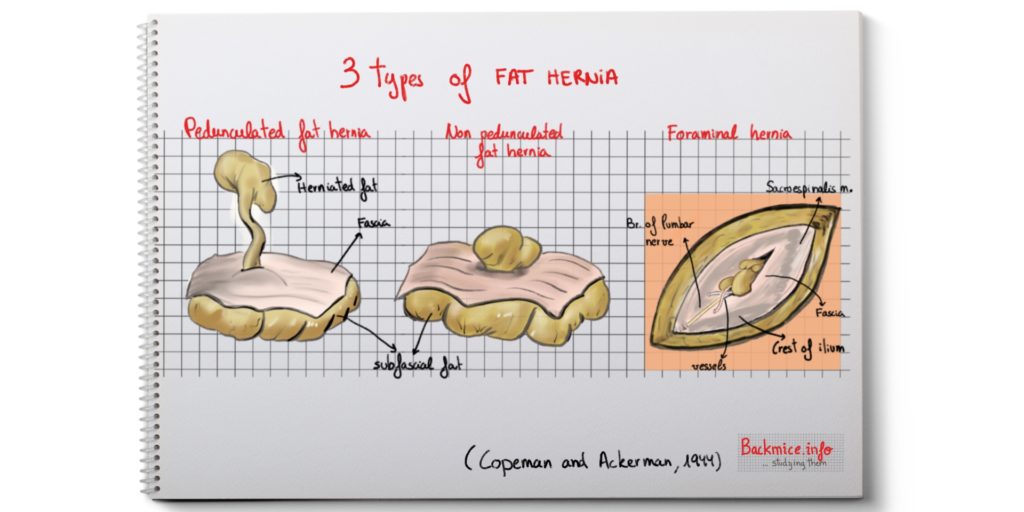

They divided the fat herniation in three types:

The non-pedunculated type of fat herniation

The fat which lies under a fascial covering is always under tension and so will bulge into a potential hernial space which may be present, either as a result of a congenital weakness or as the result of trauma. It would be increased by muscular action. If edema may occur, this tension may initiate a vicious circle, and tend to make the condition chronic. By microscopic sections from biopsies they even notice certain degree of fibrosis, which could happen in the chronified cases, and the fat hernia could become a FIBROUS NODULE.

These are the most common found in the lumbar fat pad which lies within the superficial fascia and in its extension downwards along the crest of the ilium, in the gluteal region.

These TENSE SWOLLEN FAT NODULES (back mice) can be palpated where they are sufficiently superficial. The fact that the nodule may disappear after heat and massage suggests that they are rather fat than fibrous tissue.

A variant of this type of hernia is that which protrudes in a horizontal direction as in CASE 3. It especially occurs along the iliac crest.

The pedunculated type of fat herniation

They did not find this type of hernia in the dissected cadavers, they found it in the patients who they operated on (CASE 5 and CASE 6). In the two cases the onset of pain was produced by a sudden strain several years previously. That’s why they thought that the pedicle was the LATE result of the strangulation in a hernia that originally was non-pedunculated. Its appearance is, typically, “as a polyp”. The pedicle contains fibrous tissue and a blood-vessel. The pedicle sometimes seems to be twisted.

They mention that they often found this type of hernia in the epigastric region.

The foraminal type of fat herniation

Copeman and Ackerman just found this type of hernia ONLY ALONG THE EDGES of the sacrospinalis muscles. These muscles are supplied by the lumbar nerves (from the 1st to the 3rd, the superior cluneal nerves). The lateral branches become cutaneous and pierce the deep facia at the spots where the trigger points of “fibrositic pain” occur.

They found in all the cadavers that the nerves pierce the fascia along with the vessels. There is a foramina that present a horizontal fold that seems to act as a “valve”, this overhanging fold is so arranged as to occlude the foramen on flexion of the back. They observed that the mechanism proved ineffective in certain cases and a “small tuft of fat lobules” herniated through the foramina.

In cases 9 and 10 this type of hernia was related to have caused a SUDDEN LUMBAGO. The removal of the EDEMATOUS FAT and the enlargement of the foramen proved curative.

They noticed that this type of hernia seemed to occur more with the second and the third lumbar nerves, whose foramina are not overlapped by the latissimus dorsi muscle (at least in the 14 dissected bodies).

Foraminal type of herniation was not found in the dorsal region, although Copeman and Ackerman thought that the same could happen to the cutaneous branches of the thoracic nerves that pierce the rhomboid and the trapezius.

10 CLINICAL OBSERVATIONS

Copeman and Ackerman present 10 clinical cases where the BIOPSY proved curative. The only anesthetic employed was a local injection of 1% procaine into the skin.

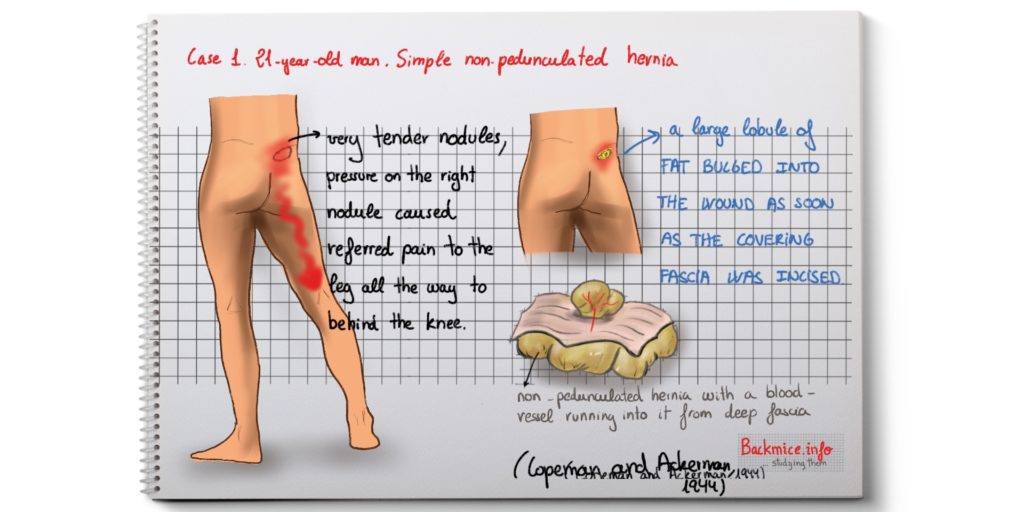

CASE 1. A 21-year-old man. NON-PEDUNCULATED hernia. SIMPLE TYPE OF HERNIA

The man had past history of rheumatic fever (aged 11) and scarlet fever (aged 14 years). After that, no rheumatic pains since then. After being accidentally hit in the head with an iron bar, he was in bed for 4 weeks. He was with sciatic pains and weakness in legs and back and he also presented tonsillitis while he was admitted in hospital. When he got up after 4 weeks, pain RELAPSED IMMEDIATELY. There was a generalized tenderness over muscles of lower limbs and VERY TENDER NODULES (or back mice) 2 1/2 in from midline and 1 1/2 inches below iliac crest.

Pressure on the right one caused REFERRED PAIN to the leg all the way to behind the knee.

They decided to explore the right nodule after transfixing it with a needle: a large LOBULE OF FAT bulged into the wound as soon as the covering fascia was incised, pressure on that fat caused referred pain. The lobule presented a blood-vessel running into it from deep fascia, but no pedicle. The nodule was removed and patient was relieved, and no recurrence occured after 2 months.

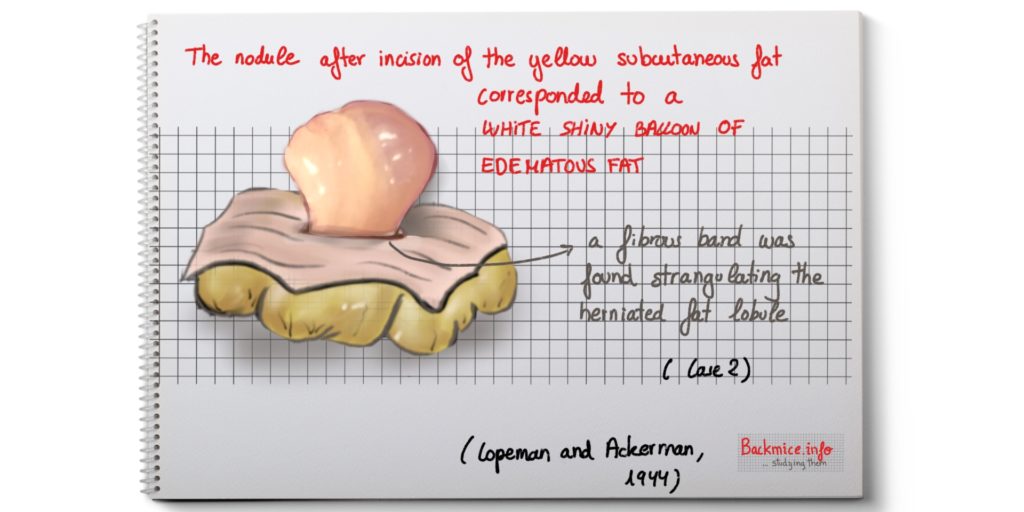

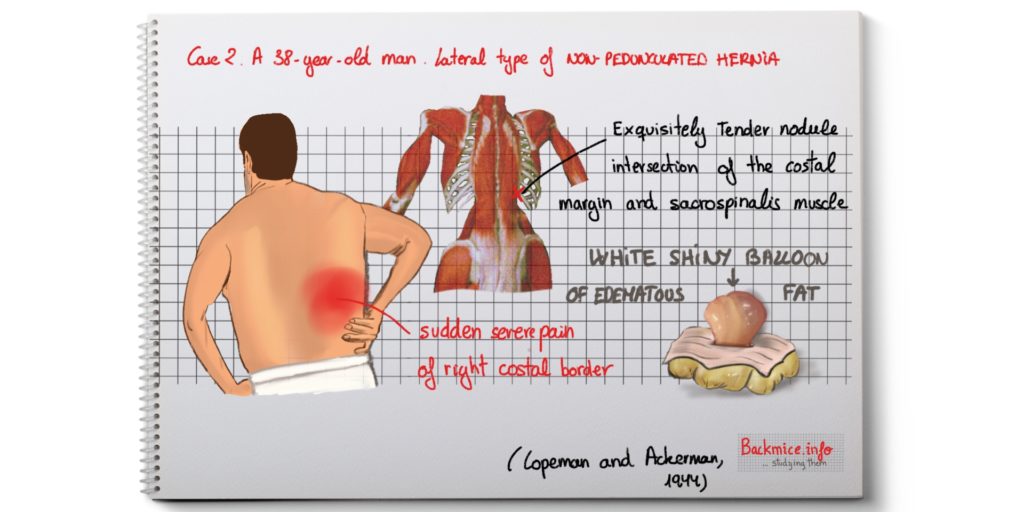

CASE 2. A 38-year-old man. NON-PEDUNCULATED HERNIA. LATERAL TYPE OF HERNIA

The man had been suffering “vague fibrositic pains” for years, mainly influenced by the weather. It became worse in the last years, and he also gained weight. He was admitted on account of a sudden severe pain in region of right costal border after a sudden movement.

By palpation, they discovered that the origin of the pain was an EXQUISITELY TENDER NODULE located in the neighborhood of the intersection of the costal margin and the sacrospinalis muscle. He could not lie down in bed. He sat in the chair for 3 nights with morphine.

Then they transfixed the nodule, after incision yellow subcutaneous fat was seen for a depth of about 1/2 inches (1.3cm), and imbedded in this was a WHITE SHINY BALLOON OF EDEMATOUS FAT. A fibrous band was found constricting it at its origin, it seems it was strangulating the herniated fat lobule. After surgical removal, the patient remained free from pain in that location, although other “fibrositic pains” remained.

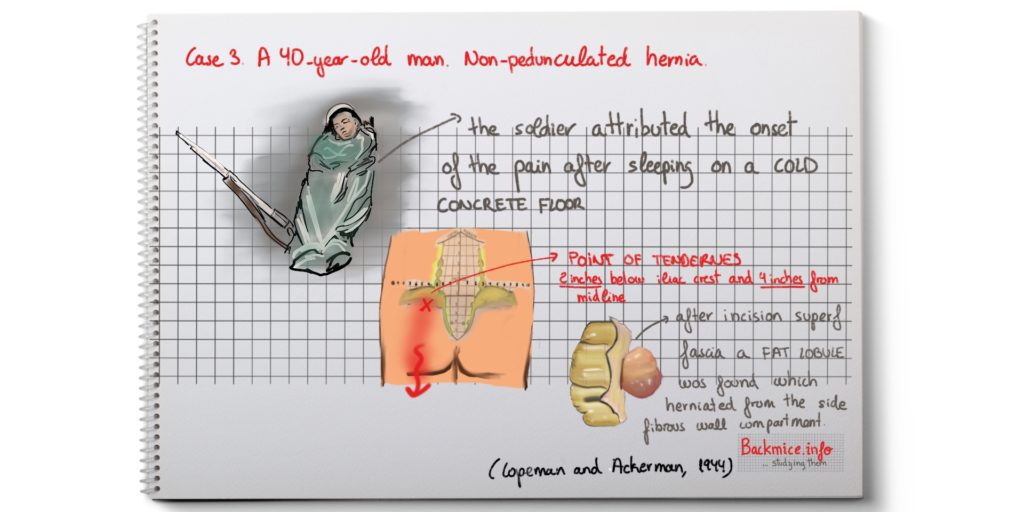

CASE 3. A 40-year-old man. NON-PEDUNCULATED HERNIA. LATERAL TYPE OF HERNIA.

No history of rheumatic pains. 4 weeks of left buttock pain radiating down back of the thigh to the ankle. He was treated in hospital for a month with no improvement. He attributed the onset of pain after SLEEPING ON A COLD CONCRETE FLOOR. Physical examination revealed a POINT OF TENDERNESS in the left buttock 2 inches (5 cm) below the iliac crest and 4 inches (10 cm) from midline. Pressure on this point reproduced sciatic pain.

They performed and incision over THAT POINT. After dividing the superficial fascia, a LARGE FAT LOBULE WELLED UP INTO THE WOUND, meaning that it was under considerable PRESSURE. When this “was pulled upon”, the sciatic pain was reproduced.

They found the origin of the fat lobule to be in the ADJOINING compartment of fibrous tissue, from which it had herniated through the side wall. A cavity the size of a cherry was left after removal. Pressuring surrounded tissue around this cavity failed to reproduce the pain. No recurrences after months.

CASE 4. A 27-year-old man. NON-PEDUNCULATED HERNIA. MULTIPLE HERNIAS.

Two years before, he suffered from severe backache of sudden onset. It was treated with heat and massage and recovered in a few days. Four days later, he was admitted in the hospital with acute hepatitis. The pain RECURRED SEVERELY in the same place, lasting for 4 days. It disappeared for two days and then returned.

They found a VERY TENDER PALPABLE NODULE about the size of a small pea at the border of the right sacroespinalis muscle 1 1/2 inches above the iliac crest (3.8cm). After an incision was made, they observed that the fat at the superficial fascia appeared to be under considerable pressure at all levels. They observed small herniations, the palpable nodule only was the culminating point. The FIBROUS WALLS between the lobules were unusually firm and the herniated lobules would be constricted by them. The fibrous walls were DIVIDED, some fat lobules removed, and the whole area “teased”. After stitching the wound, they could observe a “hollowing of the area”. But they concluded that this was not according to the amount of fat excised, but rather to the release of the accumulated tension, this disappeared after 2 days. After operation, rheumatic pain was gone, although the wound was sore.

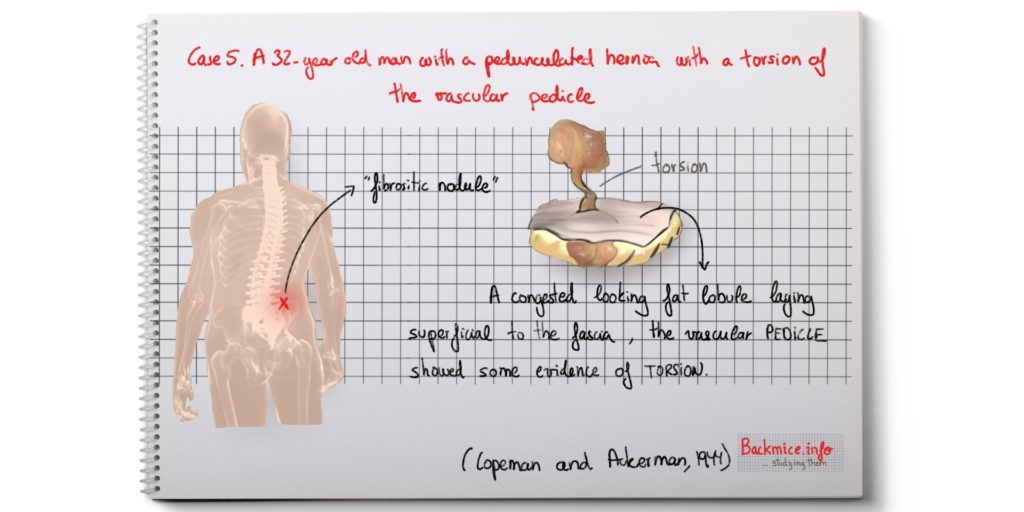

CASE 5. A 32-year-old man. PEDUNCULATED HERNIA.

The patient suffered since 1928 with severe pain in the back after a football accident. At times the pain was worse, and he had been seldom entirely free from pain. Physical treatment made the pain worse. In 1933 it was diagnosed a “fibrositic nodule” and he was told that he would always have it. Pain would be affected by the weather. And if he caught a cold, it would generally become unbearable for a few days. Pain would wake him up in the early mornings, but pain generally passed off if he got up and took a few breaths.

The present attack was started by an attack of jaundice.

An incision was made just above the nodule, just below the right iliac crest and 4 inches from midline (10cm). A CONGESTED LOOKING FAT LOBULE was found lying SUPERFICIAL to the fascia, and a VASCULAR PEDICLE containing two small blood-vessels showed some evidence of torsion. The pedicle was leading downwards through the fascia to another larger lobule that was distinct from the rest of the normal fat of the area. Compression of the superficial nodule reproduced the pain.

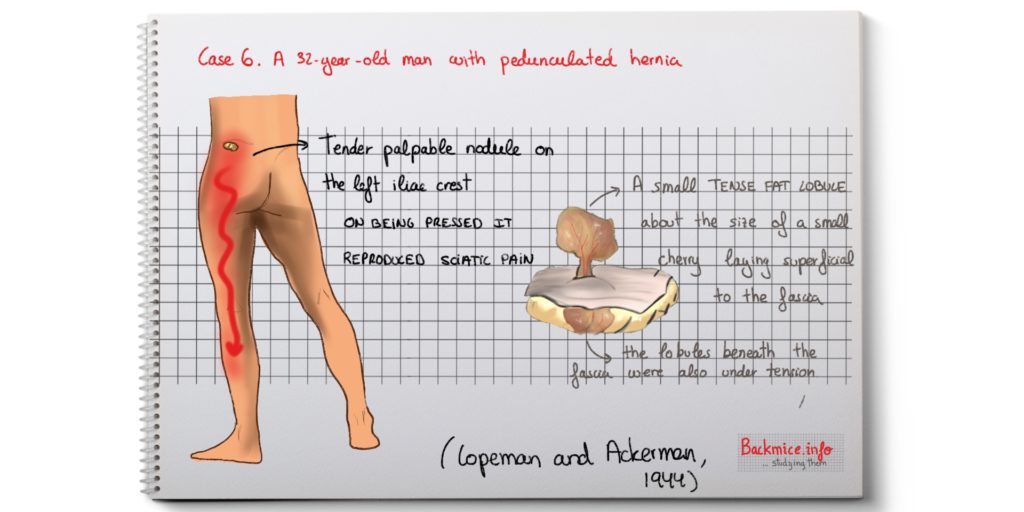

CASE 6. A 32-year-old man. PEDUNCULATED HERNIA.

No past history of rheumatic disease. The first attack of low back pain was in 1939 after he slept on the ground whilst suffering from an attack of influenza. The pain gradually got better after 6 months and it disappeared. It reappeared after 18 months with a severe cold in 1942, and since then it had been very painful. The pain radiated down the leg into the outer aspect of the calf. He did not receive any benefit from the physical therapy from hospital. He needed a limp to walk.

A very TENDER PALPABLE NODULE was found on the left iliac crest 3 inches from midline (7.6cm). On being pressed, it reproduced the sciatic pain. Also the tendon of the semimembranous muscle was found to be tender. Valleix’s points were all present and Lasègue’s pain was positive and gave rise to great pain. Reflexes with difficulty and no sensory abnormalities.

On incision, a small TENSE FAT LOBULE about the size of a small cherry was found lying superficial to the fascia. A short pedicle containing blood-vessels was seen connecting with two lobules lying beneath the fascia also UNDER TENSION. The underlying lobules were “teased out” causing pain and the superficial lobule was removed. One month later, the patient was still out of pain.

CASE 7. A 28-year-old man. BUBBLE TYPE OF NON-PEDUNCULATED HERNIA.

No past history of rheumatism. One episode some years ago of severe lumbago that lasted for 7 to 10 days. A second episode in the same place 18 months before, which lasted 10 to 12 days and got better with heat and massage. He explained sudden onset of pain 10 days before admission, first all over the back and, later, focused in one spot. They found VERY TENDER NODULES in the left gluteal region, 1 inch (2.5cm) below the iliac crest and at the border of the right sacrospinalis muscle 2 inch (5cm) above the iliac crest. The temperature, white cell count and blood sedimentation rate were normal.

Copeman and Ackerman TRANSFIXED the nodule with a needle. The incision was made at the outer border of the sacroespinalis muscle. They found several herniations through the deep fascia “LOOKING LIKE BUBBLES” that had TENSE FAT in them, which was continuous with the fat in the angle of the fascia. They also observed an also tense-looking fat lobule next to it superficial to the deep fascia. When they pulled that lobule, it gave rise to pain. They removed the fat lobules and “teased” the bubbles. No recurrence of the back pain.

CASE 8. A 30-year-old man. BUBBLE TYPE OF NON-PEDUNCULATED HERNIA.

Just past history of occasional colds and influenza. An attack of lumbago in 1942 that kept him in bed for 11 days. He fully recovered after 4 weeks. The present attack started SUDDENLY 16 days previous to admission. He thought it was in a different part of his back from the previous attack. His medical officer injected 3 TRIGGER POINTS that relieved the pain. He was driving a lorry that vibrated excessively, then starting the lorry he slipped and hit his back, this brought back the pain.

They found a VERY TENDER SPOT (no nodule was palpable) at the edge of right sacrospinalis muscle, 2 1/2 in, above the iliac crest. The marks of previous injections were seen 1/2 in above this point.

They proceeded with an incision. Inserting the finger they could feel NOTHING, although pressure reproduced the pain. Then they exposed the DEEP FASCIA, and they could observe a SMALL BUBBLE HERNIATION which felt tense. They removed together with the surrounding area of fascia. The underlying muscle was carefully inspected with negative results. They explored upwards and found similar herniations on the site of previous injections, they SEEMED to be LESS TENSE. The patient was cured after this procedure.

CASE 9. A 38-year-old man. FORAMINAL TYPE OF HERNIA.

No previous rheumatic history or serious illness. He could NOT straighten his back after he had wrenched his back and felt a SUDDEN SEVERE PAIN in his left lumbar region. He was in HOSPITAL FOR THREE MONTHS. Many types of treatments were tried, even PROCAINE INJECTIONS. He gradually got better with a less intense pain. The pain wore off with exercise.

A very tender spot was found at the edge of the outer border of the left sacrospinalis muscle. One inch (2.5 cm) above the crest of the ilium. NO NODULE WAS FELT, but the pain on pressure was severe and localized. The spot was transfixed at depth of one inch from surface. The incision was made until de edge of the muscle. Then they observed a small highly vascular TUFT of fat presenting through the fascial formanen of the second lumbar nerve (superior cluneal nerve) and two small vessels. When the tuft was pulled off, the pain was reproduced sharply. While cutting the nerve, the patient felt a pricking-character pain that was referred round to the front of the body. After the removal of the fat and the enlargement of the foramen, the patient got free from pain FOR THE FIRST TIME for three months.

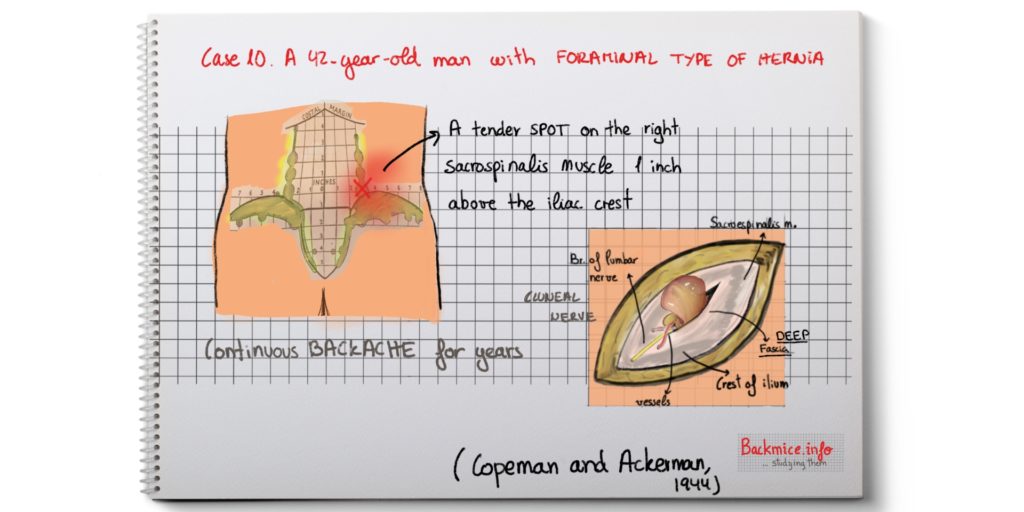

CASE 10. A 42-year-old man. FORMANINAL TYPE OF HERNIA.

No serious past illnesses. 15 years before he had an appendicectomy and, since then, he had almost continuous backache, becoming worse during severe exertion or tiredness. During the febrile period of a cold or a flu it became very painful.

A TENDER SPOT was found of the right sacrospinalis muscle 1 inch above the iliac crest. The spot was transfixed at the depth of 1 1/4 inches. An incision exposed the deep fascia. A small lobule of REDDISH FAT was found to be herniating through a patent nerve foramen. The pain was reproduced while removing the herniated fat. The foramen was enlarged. The lobule was found to be continued with the deep basic fat, lying at the angle of the fascia. The patient presented no recurrence of the pain.

Microscopic examination of the removed fat

The nodules that were removed at the biopsies consisted basically of FATTY TISSUE with young cellular fibrous tissue growing into it. The blood-vessels were congested, the walls thickened with PERIVASCULAR proliferation. In some nodules, there were patches of older fibrous tissue.

Treatment by “teasing”

Copeman and Ackerman developed a technique that they called “teasing the nodule”. First, they anesthetized the area, then they transfixed the TRIGGER POINT (previously marked with a pen) with a stout rigid needle, after injecting 10 to 20 cc of procaine 1% under the GREATEST PRESSURE possible, the point of the needle is SWEPT ROUND DEEPLY in such a way as to undercut the nodule, they also tried to divide the possible pedicle and disrupt any neighboring lobules which may be sharing the congestion. By this technique, they achieved much more lasting results than with just the technique of simple trigger point injection.

They thank Major W.H. Mylechreest for the post-morten facilities and the cutting sections for biopsy.

Published in January 2019 By Marta Cañis Parera

Reference:

“Fibrositis of the back” WSC Copeman and W:L Ackerman. QJM: An international Journal of Medicine, volume 13, issue 2-3, April 1944, Pages 37-52.